The Mayor's Race and the Mecca

Zellnor, Zohran, Cuomo, and the Knicks Playoff Hopes. Also a composting postscript.

“I hate to say this for all the Knicks fans listening,” political strategist Jason Ortiz told local reporter Ben Max on his NYC politics podcast “Max Politics,” about Brooklyn State Senator and mayoral hopeful Zellnor Myrie’s Knicks-heavy social media push. “But it’s not a great electoral strategy if you get bounced from the first round of the playoffs”

At the time of recording, the Knicks had just suffered a demoralizing loss at home against the lower-seeded Detroit Pistons. The Knicks had won the first game, so the series was tied 1-1, but the younger, scrappier Pistons seemed to have all the momentum, while the Knicks marquee superstars Karl-Anthony Towns and Jalen Brunson, both offensive geniuses and defensive liabilities, were unable to score, and seemed to have been exposed as, respectively, a fraud and a cynical, morally bankrupt foul merchant. The Knicks were careening towards an upset, their coach was about to get fired, they’d gone all-in on this roster, trading away every future asset they had, and they’d come away with a regular season juggernaut that would never be a serious contender for the championship. As things stood, Ortiz was right that Myrie probably did not want his campaign to be the 2024-25 Knicks of the mayoral race: overrated, flush with cash, but unable to even be seen as a contender, getting outshined unexpectedly by the youthful energy of an upstart insurgent.

But the Knicks have stormed back with two thrilling wins since then, taking a 3-1 series lead, and Myrie’s not the only candidate trying to draft off their wake. Zohran filmed a man-on-the-street spot outside the Garden before Game 2, and then aired his first TV ad during the broadcast of Game 3. Cuomo has dutifully tweeted commendations after each win. Even Brad Lander has gotten in on action with a feisty “LFG!!!!”, even though he, like any self-respecting Park Slope feminist girl dad, surely prefers the Liberty.

Myrie has taken it to a different level, though. He’s posted at a much higher clip than the others, including tweets after every game, an appearance on a Knicks podcast in which he talked only about the team and their prospects for 45 minutes, and a picture of him in the car on the way back from Albany making a fundraising call while watching the game on his laptop, with the caption “Get you a mayor who can do both.” He’s also the only candidate who has incorporated his Knicks fandom into his policy agenda. “Ahead of Game 2, I’m calling on the Knicks to give away 1,000 playoff tickets to working-class New Yorkers for every remaining home game,” he tweeted last week. “MSG prices continue to rise — everyday New Yorkers deserve to see their team live.”

I’ll pause here to admit two things here. First, I think the fandom is authentic. Last month, I hung out with Myrie for ten minutes at a Knicks watch party that his campaign threw, and I was impressed with the intensity he brought to a sleepy regular season bout (the Knicks were playing a depleted Milwaukee Bucks squad without a few of their starters, and they took a quick double digit lead, then went on cruise control through the last three quarters for an easy win), interrupting conversations with donors and important-looking campaign staff to saunter back to the TV and react to a Mikal Bridges three. Second, I like Zellnor Myrie! Housing affordability is the biggest crisis that the city faces right now, and he has the most ambitious plan to fix it: a million new units of housing. So as a fan of the Knicks and of bold housing policy, I should have been the perfect target audience for his pitch to make playoff tickets cheaper.

The Myrie campaign surely thought so anyway, and hoped it would be a clever way to create buzz with younger voters, a demographic that the 38-year old State Senator hopes to win from the 33-year old Mamdani, his main competition in an otherwise more senior field (56-year old Lander, the 64-year old Adrienne Adams, 65-year old Stringer, and 67-year old Cuomo). But surprisingly, this proposal faced immediate, fierce criticism from a different bloc of voters: commenters on the Knicks subreddit r/nyknicks. “I personally love when a mayoral candidate tries to score political points by doing absolutely nothing. He’s the perfect NYC Mayor!” sarcastically quipped one user, earning over a hundred upvotes. “New York and absolutely fraudulent mayoral candidates, name a more iconic duo,” another user complained. Why the harsh response? Well, some users had concerns on policy analysis grounds. “All tickets would be flipped immediately,” one user correctly pointed out (ticket resale experts disagree on whether or not this would be a problem).

But to my eye, the bigger objection underlying this backlash was best articulated by the user Historical-Cash-9316 who wrote, in response to someone pointing out that the Philadelphia Sixers had tried a similar ticket giveaway policy, “Never compare us to them lmao, it’s like comparing a Michelin star restaurant to Applebees.” Because while the fans who congregate on Taylor Swift or boygenius message boards frequently complain that tickets are too expensive, and do earnestly argue that putting some aside for true fans is a matter of moral urgency and social justice, Knicks fans love that prices are high. We play in the World’s Most Famous Arena, the Mecca, and no matter how good we are, it is important to believe that this is where everyone wants to play, and of course, where everyone wants to be. When data from the resale site TickPick revealed that the cheapest ticket available for the Knicks’ Game 1 last week cost $353 (the next highest was the Lakers @ Nuggets, which cost $228, while a fan could get into five of the other six Game 1s for under $100), Knicks fans rejoiced. Of course we did. It felt good to be number one. Zellnor’s proposals of equity and justice might be nice in some politics circles, but they are antithetical to the self-aggrandizing swagger of the Knicks and their fans.

Your mileage may vary, but this may end up being a decent metaphor for the fate of redistributive, justice-oriented politics in New York more generally. Kevin Dugan and Simon van Zuylen-Wood wrote in their indispensable New York Magazine piece “Real New Yorkers Root for the Yankees” that “New York is the richest city in the world, swaggering and unapologetically unequal. It’s not in fact an underdog, but a bully, and it’s the Yankees who embody this spirit.” The Knicks embody it too. They have not achieved the Yankees’ level of imperial success (though recently, neither have the Yankees) but that’s fine, the meanest bullies are the ones who do so to compensate for their own glaring shortcomings. And as Dugan and Zuylen-Wood point out, this swagger appeals to the working class of the city as much as it does to the ultrawealthy. From that piece: “The Yankees are both the elite team of capital and team of the working class. The plutocrat living on Fifth Avenue may root for either team, or some different squad from out of town, or no one at all. But it’s a good bet his doorman who lives in Washington Heights roots for the Yankees. This is because rooting for the Yankees is an aspirational act.”

Democratic Socialist Zohran Mamdani understands that rooting for the Knicks is an aspirational act too, which is why he steered away from proposing policy solutions to the unaffordability of Knicks playoff tickets in his pregame street interviews. I think a lot of his recent success comes from his ability to frame the socialist policies he’s running on with the rhetoric of swagger rather than of justice and morality. His policy proposals (“Freeze the Rent” “Make Buses Fast and Free”) all sound big and active and powerful, and by the standards of a DSA campaign, there’s a fascinating lack of emphasis on class politics and redistribution, compared to the sweeping “Tale of Two Cities” moral outrage of the 2013 Bill de Blasio campaign. (in fairness, there are only a few small ways the mayor can raise taxes on the wealthy, and when pushed, Zohran does support those).

Another lesson Zohran and Cuomo have learned from the Knicks: New Yorkers like winners and hate losers. As I’ve written before, Cuomo’s strength is a self-sustaining engine, people support him because they think he’s going to win, and people think he’s going to win because everyone supports him. Zohran does not have Cuomo’s poll numbers or breadth of endorsements, but through his gaudy fundraising, viral social media posts, and appearances at buzzy live events, he’s managed to “demonstrate tangible momentum,”in Ross Barkan's words, which in turn generates increasingly frenzied press coverage. Zellnor Myrie, for now, seems to have no tangible momentum to demonstrate. He’s polling between one and three percent, and his campaign looks stagnant and in danger of, as Jason Ortiz put it, “getting bounced in the first round.”

But things can change fast in basketball and politics. Two games later the Knicks are hot, the city is behind them, and after they punt the Pistons into the sun tonight, who knows how far they can go. Zellnor bought his first round of ad slots this week too, for a new 30-second spot that, to me at least, seems a lot more compelling than his Knicks pandering.

And he’s improved his Knicks pandering too! “We’re running this campaign in true Knicks style. Scrappy. Tough. Determined.” he tweeted yesterday. “And like the Knicks, we're going to win.” Let’s hope!

PS: A note on my last column on composting.

Last week, I tried to make the case that, contrary to the popular belief, city-wide composting at scale is an impactful decarbonization initiative that would avert hundreds of thousands of tons of carbon emissions every year. More than one reader reached out to me, dubious, to ask “why should we care about averting hundreds of thousands of tons of carbon emissions? Doesn’t that seem like a drop in the bucket? Does that really matter plus or minus that number, when we emit tens of billions a year globally?”

I took it as given that anyone reading my blog would agree that carbon emissions are bad and that we should try to do less of them, but it’s a fair question, and it addresses a key assumption underlying my argument, so here’s my response:

Yes, we should care. We should care a precise amount per ton. In my column, I cited an estimate of the social cost of a carbon emission at around $50 a per ton, but some recent studies have argued that it should be three to four times higher than that. It is easy to imagine the future of climate change in apocalyptic, binary terms: either we are all screwed, the oceans will rise and flood us all, and the planet will burn to a cinder, or we will figure out a way to curb emissions and be fine. In reality, we are guaranteed to end up somewhere in between, with apocalyptic flooding, wildfires, hurricanes, and extreme warming for some (especially in the Global South, but also in Florida and California), amidst a fundamentally-still-habitable earth. How many people die, how many homes flood and burn, and how much of that earth remains habitable depends on how quickly we decarbonize. Every new ton of carbon emitted points us towards measurably a worse future, while every ton averted slightly mitigates those future harms. The point of the social cost metric is to quantify the future harms (in property damaged, lives lost, economic output stifled) and give us a time-discounted price of what we should be willing to pay to avoid them.

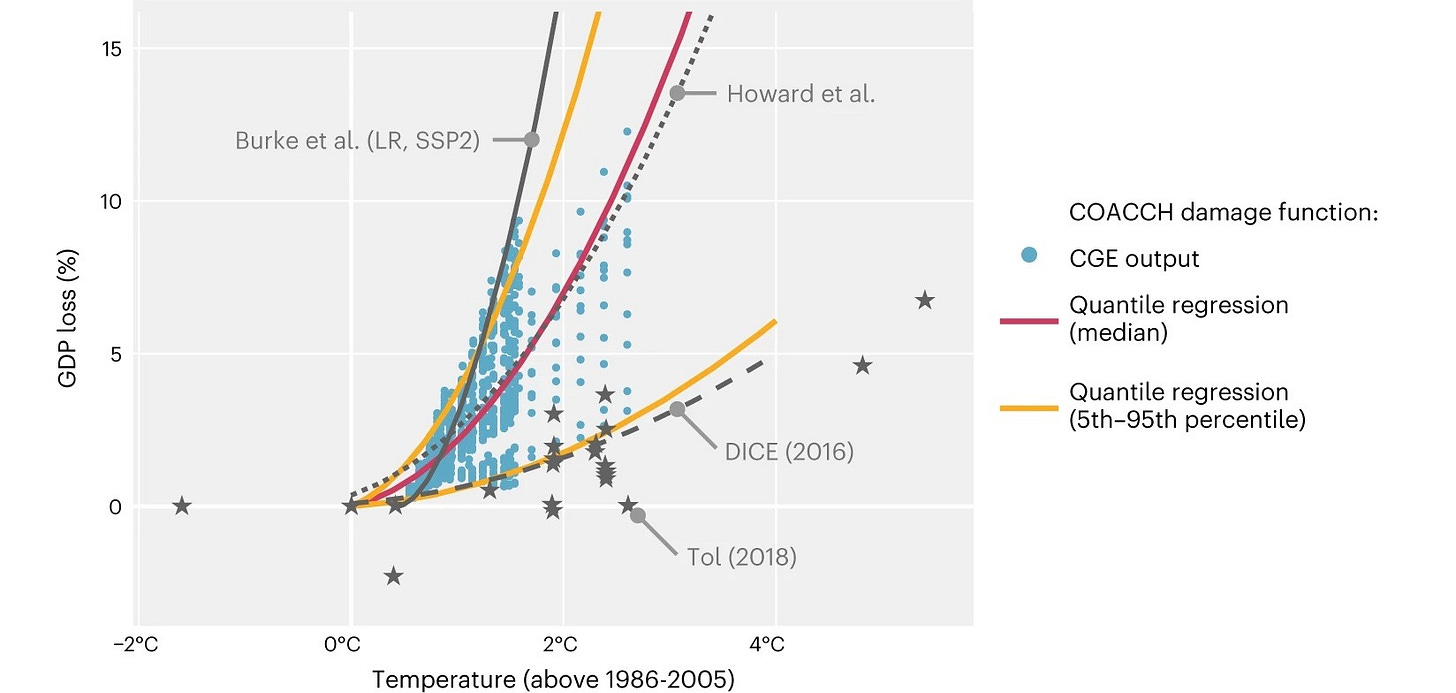

Not only that, but those harms are not linear, they grow exponentially as we add more carbon. A world where there is 2.2 degrees of warming is not 10% worse than one with 2 degrees of warming, it’s ten times worse. There are myriad reasons for this. An extra foot of sea level rise floods an exponentially larger area of land. A Category Five hurricane does exponentially more damage than a Category One or Two. A slightly worse drought can be the difference between a spark causing a controllable blaze vs. a city-destroying wildfire. All of this is encapsulated in the chart below, which shows that global GDP loss scales exponentially to temperature increase, which comes from this paper. Each line is the projection of a different impact model, and they all curve upwards, because they all agree on this basic fact.

It can intuitively feel like a 500,000 ton reduction might not be worth anything if it’s only .001% of global emissions. But this chart shows that in some ways, the opposite is true. Because there are so many emissions, because we are so far along that upward-sloping curve, the first ton we avert is the most valuable one. The second is the second-most valuable. If we could reduce our output by 10%, our future would be much much more than 10% better, we’d move to a flatter part of the curve, and the value of averting emissions would be lower than it is now.

This doesn’t mean averting that first ton is infinitely valuable. But it also means it’s worth much more than nothing to us. Conservatively, it’s worth about fifty bucks. If we can find a way to avert it for less than fifty bucks, that’s a good deal and we should do that thing.

In this case, we’ve spent most of the money already, composting will become cost-effective as soon as it scales up, and we can avert that first ton for essentially nothing. It’s incredibly frustrating that Randy Mastro is choosing not to.